영국 왕립역사학회(The Royal Historical Society, United Kingdom) 석학회원인 교양대학 데이비드 윌리엄 김(David William Kim)교수는 중국 연해주, 하얼빈과 미국 하와이가 아닌 국내 최초로 공개 국제결혼 (Cross-Cultural Marriage)사례를 탐구하여 미국인 Victor William Peters (1902-2012)와 이화여대 룻(Ruth) 한흥복 (1912-1999)이 유교적이고 식민지적 환경(1920)속에서 어떻게 서양교육과 한국현지화 사상을 접목하여 다문화 가정을 이루어 성공했는지에 대한 새로운 문화인류학적 가설을 주장하여 관련 국제 Transnational Sociology와 Missiology 학자들 가운데 연구결과가 인정받아 미국의 International Review of Mission에 출판하게 되었다. 아래 원문 (The Glocalization of Methodist Christianity in Colonial Korea: An Anthro-Missiological Study of Victor W. Peters and His Indigenous Cognition)의 일부 내용을 간단히 소개하고 있다:

Asso. Prof. Dr. David William Kim

Modern Protestant missions were launched in East Asia based on previous experiences in South and Southeast Asia. Regional nations, including Japan and China, encountered the Christian movement within the context of the global phenomena of colonialism and imperialism in the 18th and 19th centuries. While Joseon Korea had not been fully known among outsiders, the US Methodist Church, along with the Presbyterian and Baptist churches, did send pioneers in 1884. What, then, was the influence of the Methodists’ work? Who was Victor W. Peters (1902–2012)? Why was he unique compared to his other colleagues? What was his cultural philosophy in colonial Korea (1920s–1940s)? This article explores these questions through the historical records of the Christian mission to establish the Korean Methodist Church, focusing especially on the cross-cultural identity and the indigenous principles that Peters applied.

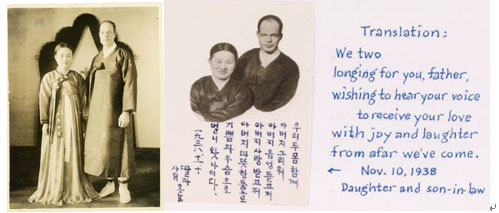

Wedding day and a postcard for Hanh’s parents

The 1920s through the 1930s was an era of socio-political transformation in East Asia. The Kuomintang’s (KMT) Republic of China (ROC: 1912–1949), which followed the Qing dynasty, tried to establish a rival government with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) for the unification of China. Japan, which had successfully modernised, launched its colonial policy of (East) Asia after the military victories of the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) and Russo-Japanese War (1904–05). The Joseon-Korea peninsula thus became the first scapegoat for the continent ambition of imperial Japan through the Japan–Korea Annexation Treaty (1910). While the geopolitical situation was progressively changing, Christian missionaries started to encounter the anti-religious policy of the Government-General of Joseon in the 1920s. Further, the American Protestants faced obstacles, such as not being able to get involved closely with local workers because they lacked local language skills and cultural understanding. As such, this paper explored the uniqueness and the impact of Peters, an American Methodist man who worked for the glocalisation of Christianity under Japan’s colonial restrictions and the pressure of Shintoism.

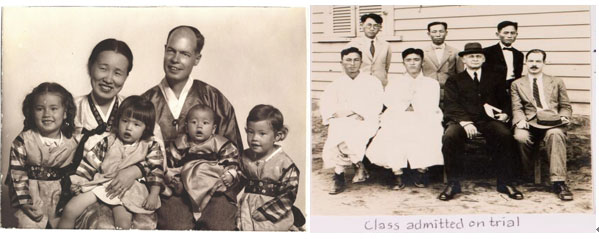

The indigenous life of Victor Peters challenged not only his foreign colleagues but also the local Christian leaders of Confucian people. His practical strategies were regarded as exemplary conduct across the Protestant movements. Whether it was a deliberated plan, or a spontaneous fate made with pure love, the cross-cultural marriage between the American man and the Korean woman became known as the first in modern Korean history. It was indeed an undeniable fact that the couple’s harmony in holding the same belief directly opened up an extraordinary opportunity for them to affect the local communities, especially Seoul and Pyeongyang. While their four children represented the fruits of two different cultures meeting and understanding one another, Peters himself adopted the philosophy of regionalism (=Koreanism) and applied it in his life as the second strategy for the indigenisation of Christianity. Peters’ Christian teachings, from one who dresses in hanbok, who eats hansik and lived in a hanok garnered less repulsion and gained more intimacy with local Koreans. A friendly relationship between Peters and any Korean could be established quickly, given that they could communicate through the ethnic language of hangul.

Yet the curious question—How much could the American Peters actually become indigenous?—is answered by his volunteer work for church-planting as the senior leader of a local church. Unlike other foreign workers, who simply could not play such a vital role, Peters’ commitment to the Kimwha Church, in particular, demonstrates the personal characteristic of him being able to live together with local people. The architecture of the church he built has a Korean-style of roof, paintings of Koreanised biblical figures and walls with which the locals become easily familiarised without a sense of difference. The education programs he helped establish, including a kindergarten and the mother’s club, offered spaces for female leaders to share their skills and abilities, which countered Confucian culture (男尊女卑, the socio-political idea of predominance of men over women). Additionally, Peters’ awareness of local issues can be seen in his relationship with Simeon Lee Yongdo, for whom he advocated coherent concept of the ‘mystical unity (合一).’ Few foreign workers were either interested or involved in the theological controversy, but the American Methodist contributed articles defending the young Korean in the magazine Korea Mission Field. Thus, Peters’ indigenous ardor demonstrated that his purpose-driven engagement had become a source of ‘soft power’ or a ‘cultural bridge’—not only between Western and Korean cultures but also among local leaders and missionaries—for the growth and development of Christianity in the colonial era of Japan’s occupation of Korea.

For more details, please see https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/irom.12433